Type safety vs. unit tests

A debate of several years...

Can unit tests that assert type safety be enough to compete against strong-typed languages?

Long time ago I came across a tweet from Bob Martin that pointed out if strong-typed languages really had the benefits that they proposed, because the safety could always be obtained by the use of unit tests. His proposal, which sparked debate, was that any particular benefit that the type system was giving, could always be replaced (and hinted that maybe should be replaced) by a set of rigorous unit tests.

I could not find such tweet anymore, since this has been a topic of debate on his twitter for a long time now. So much that his last blog post (On types) touches on this very subject again.

Twitter went crazy with that particular tweet, people from all over the spectrum of opinions and different levels of civility decided to chime in.

That particular tweet stuck with me – what was the benefit of strong-typed languages? Aside from these extra checkings that the type safety would give (which could be replaced by unit tests), everything on top was just syntax-sugar, wasn’t it?

I never came to a strong conclusion until now, where, after years of working on a particular project in bare JavaScript, I decided to rewrite it in TypeScript. Notice the particularity of these languages: TypeScript is not a standalone executable language, but rather transpiled back to JavaScript for execution. This means that the type safety it provides is not on runtime, but rather at design time, and only at design time.

The answer is: the benefits of strong typed languages outweight the benefits that only type-unit tests could provide.

Let me explain.

Say that you start with a project in a loose type language, and following good practices, you ensure that whatever object you’re working with, it can be properly used in the way it’s meant to be used.

function MyClass(param1, param2) {

function someMethod(param3) {

const param13 = param1.method1(param3);

const param23 = param2.method2(param3);

console.log(param13.method13());

console.log(param23.method23());

}

return {

someMethod

};

}

Aside from the regular tests that are needed for the proper behavior, the following unit tests would be required to assert for type safety:

- Can

MyClassbe instantiated with the wrong type ofparam1? - Can

MyClassbe instantiated with the wrong type ofparam2? - Can

someMethodbe invoked with the wrong type ofparam3? - (Also include combinations if you’re using inheritance or mixins of any kind.)

Even if not part of the unit tests for this particular snippet, these interactions also force the following unit tests to exist:

- Can

method1be invoked with the wrong type ofparam3? - Can

method2be invoked with the wrong type ofparam3? - (Also include combinations if you’re using inheritance or mixins of any kind.)

And all in all, that gets you covered. You might not have to do a lot more to ensure that you have type safety in your system, even in a language that did not ensure type safety at all. What’s even more, you can adjust these rules to you liking so that the system allows for strong-typing, prototyping, duck-typing, mixins, or whatever other construction fits better for your design. This all, within the boundaries of the language that you’re using as a base.

The only problem with this is that we don’t get immediate feedback. Sure, even if the unit tests run quickly, writing code will always go through the steps of writing, seeing tests fail, adjust for them, and move forward.

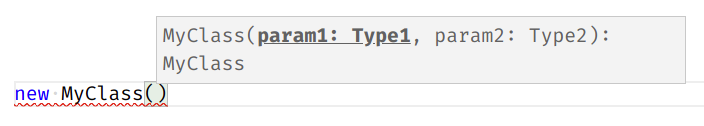

This means that writing a consumer for MyClass will involve some variation of passing parameters to it, seeing that they don’t work, and diving into the definition of the class or the tests to find out what parameters are the proper “typing” (whatever that means in this context) to pass.

This is where our process falls short.

For the sake of the thought experiment, let’s say that we include a plugin in our IDE that will do this for us, and whenever we are writing a consumer for MyClass, it will immediately point out: param1 needs to be an instance of Type1, or, since we like succinctness: param1: Type1.

At this point, we’ve reinvented strong-typing.

class MyClass {

constructor (private param1: Type1, private param2: Type2) { }

void someMethod(param3: Type3) {

const param13 = param1.method1(param3); /* method1 will only receive Type3 */

const param23 = param2.method2(param3); /* method2 will only receive Type3 */

console.log(param13.method13());

console.log(param23.method23());

}

}

The reason for this all is not particularly about the benefits that strong typing or unit testing provide. Bob Martin is right that, in theory, their capabilities are the same, and that any tests can cover for any scenario that type safety will give.

However, theory is not practice, and in practical terms, we developers have limited mental capacity. This is where strong typing shines: it abstracts us away from this back-and-forth of “am I using the right type?” and “I need another test” by just doing these tests for us.

Yes, I will agree that strong typing is syntax-sugar on what tests can already do. But so are high-level languages. Why aren’t we all writing our programs in machine code? Syntax-sugar is not a bad thing.