Death to Singletons!

Singleton.Instance.SelfDestruct();

No, I’m not talking about those that can’t find someone to be with. You’re ok in my book.

One of my favorite question to ask at technical interviews is “Can you tell me advantages and disadvantages of the singleton pattern?” I get varied responses, but while almost everybody can think of the advantages, nobody mentions the problems that come along with it. I’m going to quickly explain what singletons are and then roast them good.

What are singletons?

Singletons are a design pattern. A particular one which is pretty common because it’s very simple to implement and it’s advantage can be seen right away. Let’s start with a textbook definition (if Wikipedia was a textbook):

the singleton pattern is a design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to one object (…) Implementation of a singleton pattern must satisfy the single instance and global access principles. –

Singleton Pattern, Wikipedia

So, pretty much as it sounds. A singleton is the pattern where a single object of a particular class is instantiated. The design should force that on you, so you can have at most one single instance of the class.

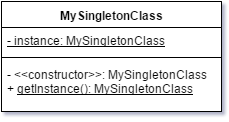

The usual design looks like this:

The usual implementation goes like this:

public class MySingletonClass {

private static MySingletonClass _instance;

// private constructor

private MySingletonClass() { }

// public accessor property that instantiates if needed

public static Instance => _instance ?? (_instance = new MySingletonClass());

}

This is a line-by-line description of the previous piece of code:

- Line 1 is the single instance that the system will have. Since any instance of any other class is very likely to be duplicated for some reason and that would break the pattern, we make it static. Also, we want it to be private so that we can control when it is instantiated.

- Line 5 is the constructor. It may contain some logic. Regardless, we need to include it so that it can be made private. Then, no other class can execute a

new MySingletonClass(). - Line 8 is the one that exposes the instance. I implemented what’s called lazy-initialization. Here’s how it works:

- It needs to have a global, single-point access. Bam.

public static. It can be accessed by just usingMySingletonClass.Instance. - It is a property. This is the C# 6 syntax sugar for getter-only properties. The body of the lambda is the value that’s returned.

- It tries to return

_instance. - If

_instanceisnull(because it may have not been created yet), it will return the result of_instance = new MySingletonClass(), which saves the value for later. This is valid because this code is in the same class, so the constructor can be accessed even if it’s marked asprivate. - Next call will just use the value of

_instanceand return it.

- It needs to have a global, single-point access. Bam.

That’s it. That’s all that there is with a Singleton.

What’s it good for?

There might be a situation in a system where you need by design to have a single instance of a particular class. This is a simple way to achieve that restriction design-wise, and it’s as simple as it looks. Accessing the instance and operating it is as simple as MySingletonClass.Instance.DoMyStuff(). You can do that from static methods or from instance methods. You can do that from any place that has access to that class. Simple.

What’s it NOT good for?

Oh boy, you asked for it.

Unit Testing

Since the state of a singleton is at the static definition of a class, the state for the singleton is preserved through the general runtime of the application. Trying to unit test it in a way that needs to regenerate it for every run means that static becomes a problem. This is, unless there’s a way of removing the class definition from runtime, or implement some kind of disposing into the singleton itself. But this is the opposite intention of the design, since the singleton lifecycle is meant to be done inside the singleton only. Doing otherwise means that the instance can be thrown down or regenerated at each point in the program execution. Technically speaking, this will still be a singleton, but it’ll generate problems for managing of such lifecycle, which consumers of the singleton mostly don’t (and shouldn’t) care about.

Dependency Injection

Again, since the singleton manages its lifecycle internally, and the constructor is private, it is difficult to be injecting stuff into it. This problem can be circumvented by registering a global dependency injector that the singleton calls. Using a Service Locator is solving a singleton problem with another singleton, and this is where the downward spiral begins.

Assuming that problem can be solved by configuration, frameworks or any system of preference, there is a second challenge: the singleton initialization can happen as early as the class is referenced. This means that the DI setup needs to be done right away or we’ll enter a fight against initialization orders in the static realm. We’re going to end up fighting our own runtime framework implementation details. Not a good place to be in.

OOP

State at a static level – is state meant to be had for a class? While not incorrect, this is usually a code smell of something that should be an object. Theory goes that state of something is a particular instance of it. It’s an object with internal state, so that the object can mutate and act accordingly.

The implementation of a singleton will likely be in the instance of it, but the state of the pattern itself is tied to a static implementation, because it’s the way that most languages allow for a single-instance-by-design, and a global point of access.

Initialization

If data is needed from the outside of the singleton constructor, where should it be retrieved from? Should values be passed every time that an instance is requested, just in case it needed to be initialized? This is awful.

Otherwise, some kind of “initialize” routine needs to be called before, like if it was a constructor (which can’t be called because it’s private). This mimics static constructors, but better because they can be easily controlled. Using static controllers directly would be a huge problem. Also, it’s imperative that this routine is called before the actual instance is used.

This is just asking for a race condition to happen.

Concurrency

For multi-threaded systems, the dangers of static state are well-known. And while the state of a singleton is in an instance, the instance is accessed from a static context. Here the singleton has static written all over it. Literally.

Lifetime

As I mentioned before, the lifetime of a singleton is meant to be handled internally to the singleton. Furthermore, the lifetime of a singleton is a pretty simple one: initialized when requested (or when referenced), then is kept alive forever.

This makes it difficult to recover from failure scenarios. It makes it difficult to dispose of resources. It can’t be, of course, garbage-collected.

Intent

Are you really really sure you need a single instance bound by design? I mean, isn’t there any situation where you may actually need to instantiate a second copy? Not for unit testing? Not for regenerating from internal exceptions? Not for releasing resources?

If you actually need any of those, a Singleton becomes a nuisance to you. Of course, you can always stick Regenerate(), Reset(), or Dispose() methods in it, but it defeats or stains the purpose of a single instance. So then, why do you have singletons in the first place?

But why?

I think that most design patterns follow a set of conventions to solve a problem, and it allows consumers of those patterns to benefit from it. The pattern is in the design itself, and the inner workings are the states of each of the classes involved. Singleton is slightly different: it mixes state with API, where it exposes a single global access through a static endpoint, but static was not intended for this usage, but rather for things that are, you know, static.

This mixture of class-state and consumer API is what gives us problems when we want to have consumers of different scenarios, likes the ones I talked about.

It’s not evil per se, but you should know about the consequences of the design you’re choosing.