Correlation ≠ causation

But causation ⇒ correlation|

In my earlier post I explained how certain type of machine learning models, specifically neural networks, find the correlations between two sets of values. For predictive models, we feed correlated variables to train our models. However, sometimes, we don’t know if or how variables correlate, and part of the machine learning intelligence is to actually find that out.

Data Mining

The concept of data mining is pretty much described by its title: dive into the data and try to find what’s meaningful about it. Lots of hidden relationships are buried in the statistical models that data intrinsically has – it’s just that we don’t see it as clearly as the data itself.

It is tempting, once a correlation is found, to try to explain a certain phenomenon. Or claim that we have discovered a new piece of how the world works, but it’s not always like that. However, correlation _is _information too, and it can be used for good purposes – but it is not the same thing as finding a causation.

Correlation vs causation

It is a common problem in scientific discussions (or even regular day-to-day fact checking) that correlation and causation mix up. Pretty much every day we encounter claims that combine the two.

**Causation **is the relationship that two events have when one sets the sufficient circumstances for something else to happen. As an example, pushing a jar off the table is reason enough for it to fall down: the former caused the latter.

Correlation is the relationship of two events (or pieces of information) that seem to be related, go together – even if they’re displaced in time. A good example of these are usual headlines that we find in news, like “Intelligent people eat more chocolate, new study finds”. While the title implies it, it does not directly indicate that the chocolate is the cause for intelligence, or that the intelligence is the cause for eating more chocolate. It is possible that these are two variables that are correlated by a third one, one that causes (directly or indirectly) the two of them. A real life example is why alcohol drinkers usually earn more money, and the hypothesis there tries to explain the correlation by assigning a third variable (social behavior) as the cause for both.

However, correlation does not imply causation – it is possible that two variables just share the same probability distribution and look really related in time, when they are not. Awesome examples can be seen at the Spurious correlations website.

But correlation might be pointing to a causation

And this is the scientific glory of data mining: it may help finding causations where we didn’t know there was one – finding correlations may point to causations we didn’t know about.

Let’s theoretically play with this example, taken from Wikipedia. I haven’t fact-checked it, but it will still be a good example to discuss.

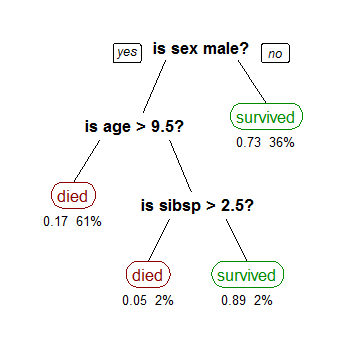

This is a decision tree that shows the relationship of three variables to how likely a passenger was to survive the Titanic accident. This is how to read it:

- If the passenger was not a male (for simplicity, let’s assume female), (36% of the population) she had a 73% chance of surviving the accident

- If the passenger was a male and he had age higher than 9 and a half, (61% of the population), he had 17% chance of surviving

- (etc.)

If you want to check the actual data breakdown I came up with, based on the Titanic data, check this gist. However, this is not really the important part.

The important piece here is that we’re seeing a certain correlation: women, children or people with families had a bigger chance of survival. Of course, we know that these facts should not have a big impact in regards of survivability in an open-sea accident. So, what is this correlation telling us?

This correlation is telling us that for some reason, women, children and people with families had a higher chance of survival. It kind of rings a bell, doesn’t it? Like the old saying “women and children first”? Interestingly, Wikipedia covers on the subject: “Women and Children First”. Let me take an excerpt (emphasis mine):

The phrase was popularised by its usage on the RMS Titanic. The Second Officer suggested to Captain Smith, “Hadn’t we better get the women and children into the boats, sir?”, to which the captain responded: “put the women and children in and lower away”. The First (Officer Murdoch) and Second (Officer Lightoller) officers interpreted the evacuation order differently; Murdoch took it to mean women and children first, while Lightoller took it to mean women and children only. Second Officer Lightoller lowered lifeboats with empty seats if there were no women and children waiting to board, while First Officer Murdoch allowed a limited number of men to board if all the nearby women and children had embarked. As a consequence, 74% of the women and 52% of the children on board were saved, but only 20% of the men. Some officers on the Titanic misinterpreted the order from Captain Smith, and tried to prevent men from boarding the lifeboats. It was intended that women and children would board first, with any remaining free spaces for men. Because not all women and children were saved on the Titanic, the few men who survived, like White Star official J. Bruce Ismay, were initially branded as cowards.

And this might be a suitable theory that is the causation that we were looking for. This is the hidden causation that our correlation might have had under it all along.

Conclusion

Correlations are another set of facts – another set of “contexts” on which we can analyze certain data. Causation is what provides meaning to it, but finding meaning where there is none is always easier with context. Data sciences, and specifically data mining, has been getting better at finding these facts where we couldn’t.