The future of work, aided by AI?

How machine learning algorithms may take on our work

I recently came across the article Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence, by Shan Carter and Michael Nielsen. I’d like to tell you a bit about the ideas that this essay mentions, and a few interpretations of my own about them.

AI vs. IA

The article starts by describing the relationship and difference between AI (Artificial Intelligence) and IA (Intelligence Augmentation). The first one aims to create artificially intelligent agents, whether it is mimicking biology or by pure mathematical constructs, while the latter attempts to be a tool that can aid on existing intelligence to push it further. Examples of AI lie among all the autonomous tools that we’ve built, like automatic chess players or Go players. Examples of IA are pretty much any machines that we’ve built that help in our tasks.

That’s a pretty broad definition, Still, you will easily understand it when you compare a technological society like ours, today, to not-so-technological societies like ours, some time ago. Now pretty much everyone has a smartphone with camera, GPS, map guidance and instant messaging, and we’ve been able to focus our brain power on other matters. Instead of remembering phone numbers or how to get to a certain place, we’ve shifted our attention and time to other tasks. Imagine what truly driverless cars will do to economy, once that hour of daily commute can actually become productive work.

AI and how it works

The essay then talks very superficially about how artificial intelligence algorithm works. Most of what we call machine learning are actually complex intelligence-based problems that are reduced somehow to optimization-based problems, that are then reduced to search-based problems.

What this implies is that, in the solution space of a particular problem, every combination of approaches will yield a result, and such result is more-or-less desirable according to a metric we decide to evaluate it on. IBM’s Watson was evaluated on how correctly it answered questions in Jeopardy, while the mapping software is evaluated on how correctly it predicted the shortest path and the time it would take you get to your destination. This is what we call our “cost” or “error” function – let’s go with error function right now, as it will be easier to understand.

If you were to put these combinations of inputs and error values from our function into a graph, you’d find that it moves up and down, and it has mountains and valleys. All of the algorithms are trying to find the bottom of the valleys: the places where the error is minimal. That’s how they become search problems.

The amount of variables that are involved is what’s called dimensionality: each of them is a dimension to consider. If you were to graph one variable and the error function, you’d have a two-dimensional graph, because the first variable already takes up a dimension. To graph two variables and the error function would take a three-dimensional graph. You get the idea.

Vectors as emergent properties

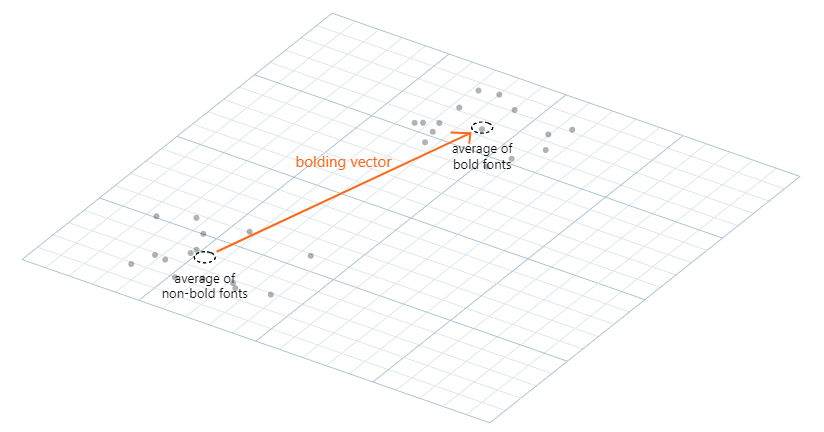

While the algorithm finds a way to map a bunch of inputs to their output in the least error-y way possible, it will have learned that some variables need to change a lot and some others not so much. This creates a relationship between the change in the variables and the properties that are being transformed.

The article explores this in the example of a font-transformation algorithm. The algorithm learns on its own what it means for a font to be bold or italic, purely based on existing examples, and then it applies the transformation automatically to any font, even if it hadn’t seen it before.

Here’s where things get interesting: the algorithm will apply the transformation of “boldness” or “italicness” to the input variables, having found a mathematical representation of a property that exists in the real world. The machine has learned an internal vectorial representation of “boldness” or “italicness” (with a certain amount of error, of course).

Emergent properties as domain-specific heuristics

This “boldness” that the algorithm has learned to apply is not a simplistic approach on how many black pixels a font needs to have, but it rather does contain some useful rules that real designers apply when creating fonts. In this example, the algorithm has detected (again, on its own) the heuristic (guideline) of preserving negative space.

This is very important: the article then suggests that with sufficient data, any machine learning algorithm may learn enough complex domain-specific knowledge to apply it. They provide a second example on shoe design based on sketches and how several properties of shows are automatically adjusted, same as how a designer would do, when certain other properties are changed in the sketch of the desired shoe.

Augmenting human intelligence

And this is where we can go back to the original concept: if algorithms can learn enough sophisticated domain rules, it can become as useful enough to create new domains entirely, by doing our current intelligent work for us, and leaving free mental time for us.

How would that be like? Let’s start with the same example they provided: imagine fonts could be created entirely by machine intelligence, based on what we tell them we want as a result. Designers wouldn’t have to deal with the details of creating the fonts, but only specifying the right properties – which implies, the bar for being qualified to create good fonts would be a lot lower. Suddenly, not only designers would be able to create new beautiful fonts.

And yet, this example just shows something that we’ve already experienced. Think about how you can study to become a programmer, and a hundred years ago the concept didn’t even exist. Or how you can apply to work at NASA and help searching life in Mars, where 50 years ago we had taken a few steps on the Moon. The advance of new technologies is pushing forward what each of us, inside of our lifespan, can do.

Let’s go with examples in another perspective: imagine you didn’t have to drive anywhere anymore, because driverless cars already took care of that for us. What would you use all that new time for? Imagine if your work was automated and instead of doing it, you’d just have to supervise it was done correctly. How would your work change, how would your mental space change about it? What would you focus your mental energy in, if not in every detail that you currently have to deal with?

What about creative work?

The essay explores two big options. One of them is the one we’ve discussed already: because machines could automate the dull work, we could move on the become more creative and create more branches of human creation, expanding culture and changing more what society gives us. This is the idea I’ve also explored so far.

The second option is for machines to be creative themselves. This is purely hypothetical at this point, but let’s go back to solution vector spaces: if the solution to our problem lies in a particular path of that vector space… wouldn’t creativity then (literally) be lateral-thinking around that vector?

What if we allowed our algorithms to deviate from the pre-provided assumptions that we fed it, and it still found proper solutions to the problems we posed. They do still have error functions on which they could be measured. Would that count as creative thinking? While the answer is not pretty clear, let me show you an example on how this might work.

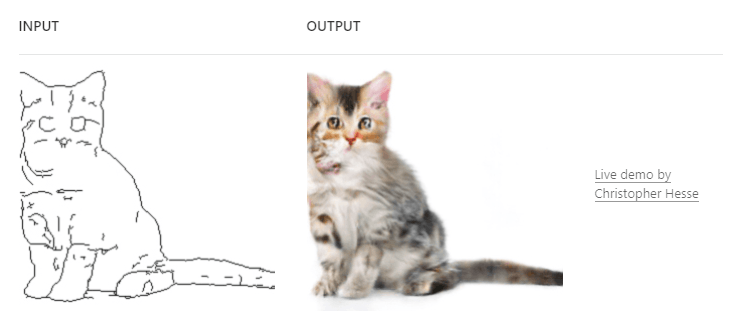

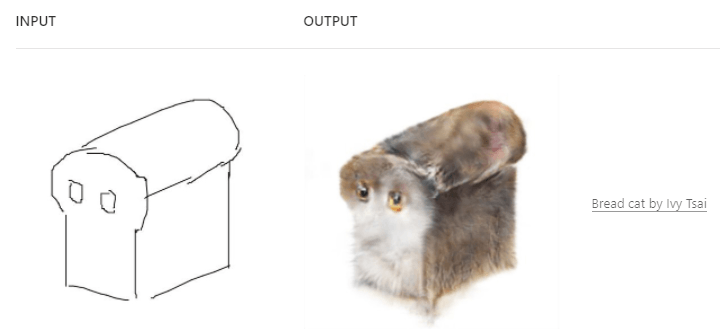

If you haven’t played before with pix2pix you can give it a try now. It’s an image generator that takes images (sketches) as input and provides more complex images (full-color) as output.

In this example, you can clearly see that the algorithm learnt to relate a cat-shape to a cat-full-color representation. However, what if we just stopped assuming what a cat-shape is?

Is this just an algorithm-failure, or creative work? Debatable. What about fauvism and dadaism? What about rock and roll or electronic music? You get the idea.

In this example, the “defiance” on the assumptions was provided by a human, but it would not be very difficult, hypothetically, to allow algorithms to deviate from these constraints and to explore more of the latent space, as the article explains it. While we’re still in the realm of speculation, it is not entirely fantasy. There have been cases of automated agents making discoveries, or finding simpler (creative?) solutions to already known problems.

The article concludes that the aid to creative of work is one of the features that will revolutionize humanity. Quoting:

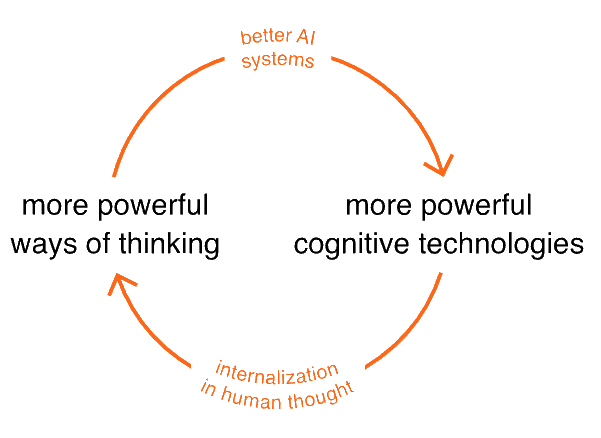

We’ve described a third view, in which AIs actually change humanity, helping us invent new cognitive technologies, which expand the range of human thought. Perhaps one day those cognitive technologies will, in turn, speed up the development of AI, in a virtuous feedback cycle: